There have been Jews in Morocco for over 3,000 years, longer than there have been Arabs in the area. Even in the ancient Roman ruins of Volubilis, there are traces of a synagogue. Today, however, most of the synagogues are as deserted as the remains of this ancient civilization. Many are still maintained by the government and the King, but most are for tourists and pilgrims, and they rarely hold services. In 1950 there were more than a quarter of a million Jews in Morocco, but today there are maybe 2,000, and most of them are in the big urban areas of Casablanca and Marrakech. The Jewish people of Morocco have left, most for Israel, France, or Canada and the U.S. The old country, Morocco, however, remembers them. In every city you can find a mellah, an old Jewish quarter or ghetto. Moroccan antique shops are still stocked with Jewish handcrafts and artifacts, even menorahs and mezuzahs. My professors would point out that so much of the "traditional" Moroccan culture, the artwork and the music, has its origins in the Moroccan Jewish community. Every tour guide in every city will say, "This is a place of respect and cooperation for every person, regardless of religion! Jews and Muslims lived here together as friends for many years."

As a young Jewish woman going abroad to a Muslim country, many people would ask me if I was worried, if I would disclose to my teachers and host family that I was Jewish, if I was likely to face anti-semitism. That could not have been farther from the reality. Moroccans love their Jewish history, and they are proud of it. Judaism is even protected under the Moroccan constitution (as of 2011) and the King's title of "Commander of the Faithful" explicitly refers not just to Muslims, but to Moroccan Jews and Christians as well. Every Moroccan who learned I was Jewish would expound upon how, "All people are really one and the same, we have to get along, as Jews and Muslims did here for centuries," and they would then ask if my family was of Moroccan descent (I regret to say we are not). I felt safe and welcomed. In some ways, it was so easy to be Jewish in Morocco. In other ways, it was very hard. I had to work to find Jewish life, a community where I could still practice my religion.

There are fewer than 50 Jewish families in Rabat today, but the synagogue turned out to be on my walk between home and the IES Abroad Center, and it was open every Friday night.

The outside looks like an appartment building, but the inside is clearly a synagogue, with modern seating and a ner tamid, the eternal flame, still lit. It's a traditional synagogue with a separate women's section, and on any given Friday Shabbat service there is no one in the women's section, and not enough men in the main section for a minyan, a quorum.

A little further down the street is a butcher's shop, and it took me a month or so of walking past it to even notice the sign in Hebrew at the back advertizing it as a kosher butcher.

David Toledano is the man in charge of the Jewish community in the capital city. He and his wife, Lisette, often host visitors from the rest of the Jewish world when they come to Morocco. I was lucky enough to enjoy their hospitality for Purim, Passover, Mimouna (a Sephardic holiday celebrating the end of Passover), and several shabbats. Both of them come from big Moroccan Jewish families, but they are now the only ones left in the country. Even their children have all moved to Paris or California. David speaks as if he expects this generation to be the last Jewish community in Rabat. Lisette says, "I will close the door behind me on my way out."

The Toledanos introduced me to Moroccan Jewish traditions, so different from the Ashkenazi-American ones I know from home. There are really two sorts of Moroccan Judaism: the "Berber Jews," those who have been here since before the Arabs came in the 700s, and the Andalusian Jews who fled from Spain at the end of the 15th century.

In Marrakech, where there is still a small Jewish population, they have all moved out of the mellah and into the modern parts of the city. The old neighborhood is still there, and the "Jewish" spice markets are still closed on Saturday for Shabbat.

And the streets still bear Jewish names, such as this one, "Talmud Thora," probably the name of the old synagogue.

In Essaouira, however, the mellah has been mostly destroyed. The neighborhood, at the edge of the old medina, lies forlorn and abandoned.

Although the port city of Essaouira (formerly Mogador) used to be majority Jewish, no Jews have lived here since the 1960s.

Two synagogues still stand in the mellah, and they are open to visitors.

Although the insides of the synagogues are maintained, the surrounding area stands in sharp contrast to the beautiful beachside, touristed town of Essaouira.

The city of Fez is considered the spiritual capital of Morocco, and that goes for Judaism, too. The restored synagogue, Ibn Danan, sits in Fez's mellah. The walls are hung with photos of the life of the synagogue in days gone past.

This photo shows a group of men and boys learning together....

...and here is the same place in the synagogue today.

Fez has one of many Jewish cemeteries scattered all over the country.

The tombs are blindingly white in the 100°F sun, and the sounds of spoken Hebrew float in from buses of Israeli tourists.

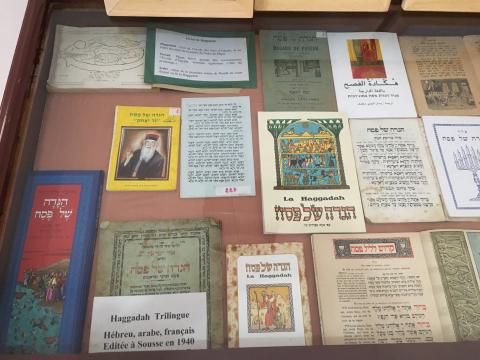

The other place to encounter the history of Moroccan Judaism, besides old synagogues and cemeteries, is the Museum of Moroccan Judaism, the only one of its kind in the Arab world, in Casablanca. Casablanca has the largest population of Jews still in the country, probably around 1,000 people. Here there are Jewish books published in Hebrew, French, and Moroccan Judeo-Arabic.

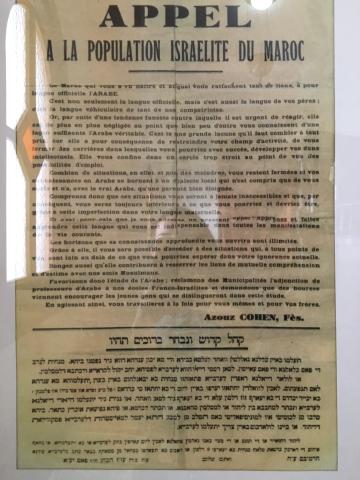

Here is a call to action, published in a newspaper in 1933 in French, calling on Jewish Moroccans to learn to speak Moroccan Darija (colloquial Arabic) rather than Judeo-Arabic, the better to communicate with their Muslim neighbors. Today, Judeo-Arabic is unused as Moroccan Jews speak mainly French.

One of the photos hung on the wall is this picture of King Mohammad the V (third from the right), right after his return from exile in Madagascar, visiting with three Grand Rabbis and two prominent members of the Jewish community. The current King's grandfather, Mohammad V, is loved and remembered in Morocco for being the King who led the country to independence. For the Jews of Morocco, he is also remembered for protecting the Jewish population from deportation during WWII, when the French protectorate would have handed the Jews over to the Germans. The King insisted that the Jews were his citizens and therefore under his protection.

The glass cases are full of clothing, furniture, artwork, and artifacts—all that the Jews left behind. What was once a thriving culture is now dwindling, visible mostly in museums, historical sites, and cemeteries. Today, looking at the remains of Judaism in Morocco feels like looking at a well-preserved ghost town. It feels a bit like walking through the ruins of Volubilis. The evidence of this culture, this history, is everywhere, but that time is over and the people are gone.

Sarah Mamlet

<p>My name is Sarah, and I'm from New England but I study psychology (and math, and religion, and everything else) at Vassar College in the Hudson Valley. When I'm not doing schoolwork, you can find me singing in a choir, at ballet class, or binge watching TV shows with my friends.</p>