There’s nothing unique about the Molukkenstraat transit stop. Buses and trams continuously collect commuters from its four shelters, one of which hosts a map of the nearby streets. Such maps appear at every transit stop in Amsterdam, but some of the names on this particular map decidedly do not sound Dutch. Balistraat, Sumatrastraat, Tidorestraat. Ceramplein, Javaplein, Timorplein. Ambonstraat, Borneostraat, Halmaheirastraat. And of course, Molukkenstraat itself, located at the centre of the Indische Buurt neighbourhood in Amsterdam-Oost.

Several Amsterdam neighbourhoods revolve around themes. The famous Jordaan district takes its name from the French jardin or garden, hence the floral tones of its streets - Bloemstraat, Rozenstraat, Laurierstraat. In the Apollobuurt, Beethoven, Chopin and Mozart, and Wagner rub shoulders; in the Watergraafsmeer, Archimedes, Galileo and Pythagoras are united. Other Dutch cities conform to these patterns; the Muziekwijk in Almere looks like an orchestra seating plan and there’s a district in the Hague devoted to fruits and vegetables. As Anabelle Goulette from IES Abroad Amsterdam notes, such street names “are great for orienting yourself within a city.”

But the Indische Buurt is different. It references real places, inhabited by real people, with complex and difficult stories of which Indische Buurt residents may never become aware.

****

The Moluccas or Maluku Islands lie over 12500 kilometres from the Netherlands, in the middle of the Banda Sea. Among the southern islands are Ambon and Seram; Halhamera and Tidore are to the north. To the south is Timor; to the west, Borneo, Indonesia and Sulawesi; further on, Java and Bali.

Today the Maluku Islands are remote, known for their high biodiversity and tourism opportunities; residents mainly practice agriculture, fishing and forestry. From the 15th century, however, the Banda and Molucca archipelagos were known to multiple colonial powers as the immensely valuable Spice Islands, supplying nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves.

In the early 17th century, the Dutch convinced Bandanese leaders to sign a treaty which gave them a monopoly on nutmeg trade in the islands. Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the future fourth governor-general of the Dutch East India Company, arrived on the islands in 1621. When the Bandanese resisted the Dutch monopoly, Coen ordered the massacre of the majority of the Bandanese population - an estimated 13,000 to 15,000 inhabitants. Survivors were forced into labour on the nutmeg plantations or shipped to what is now Jakarta as slaves. Coen continued to consolidate Dutch control of the East Asian archipelagos through whatever means necessary and was seen as a hero.

Dutch involvement in the archipelagos continued to the 20th century; although the islands currently belong to Indonesia, there have been repeated contestations over their independence. 12,500 Moluccans who had served in the Dutch colonial army (KINL) were repatriated to the Netherlands in the 1950s, where after much struggle and tensions, they were able to establish a community in Hogeveen.

As for Coen, a mass murderer, a port, a tunnel, a pub and five streets in the Netherlands are named after him. This was also the case for a school in the Indische Buurt itself, but it was renamed in 2018 after prolonged protests from the surrounding multicultural community. Coen’s northern hometown of Hoorn has hosted a monument to him since 1893; only in 2012 was a plaque added that mentioned his massacre of the Bandanese and acknowledged that “according to critics, Coen’s violent mercantilism in the East Indian archipelago does not deserve to be honoured”.

****

Una Bergin, who teaches Dutch language and culture at IES Abroad Amsterdam, grew up in the Indische Buurt. “The ‘Indische Buurt’ street names sound very familiar to me and I didn’t think anything of it other than [that] these are islands and places far away, like Java, Bali, Borneo etc,” she said. “I didn’t learn that much about the Dutch colonial history in the former East Indies until later.” Nevertheless, she experienced connections to the region “through the street food, kids in my class with a ‘Indische’ background and the kids museum at the Tropenmuseum.”

Flor Macias Delgado of IES Abroad Amsterdam says that she “definitely noticed the names” and that they always made her feel uncomfortable. “In the West/De Baarsjes a lot of streets are named after "discoverers" aka colonizers, and walking through Columbusplein irks me,” she explained. “Lots of streets also have plaques explaining the achievements of the person [whom] the street is named after, and the language in them is upsetting to say the least.”

Controversial names are scattered throughout Amsterdam and the Netherlands; as world events and the narratives about them are transformed, attitudes towards the names change too. After the Allied victory in WWII, a Stalinlaan was established in Amsterdam; it became Vrijheidslaan (freedom avenue) following the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Streets in Amsterdam’s Transvaalbuurt were named after Dutch colonists and heroes of the Boer War such as Paul Kruger and Andries Pretorius, which was highly controversial given that the Dutch had a colony in South Africa in the 17th century, and created policies that were later used during apartheid. Other locations honored Witte de With, a ruthless Dutch colonist from the same era as Coen.

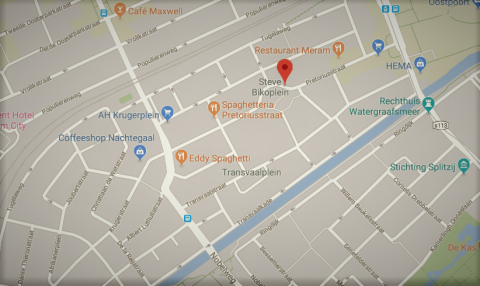

There has been some pushback against such names and monuments. Una’s father was a South African immigrant and both her parents were activists in the anti-apartheid movement that took place in the Netherlands during the late 70s and early 80s. According to Una, the activists went to the Transvaalbuurt “with ladders and glue and pasted all over all the Dutch names with the names of Mandela and his allies. They did this at night and got quite some attention”. While the reactions from the neighbourhood were both angry and supportive, what was one Pretoriusplein is now the Steve Biko plein, honouring Steve Biko, a South African activist who was murdered in police custody in 1977. Nevertheless, Krugerstraat and Pretoriusstraat remain.

In recent years, says Flor, “There has been some talk about renaming some of the streets, as they glorify mass murderers.” Dutch political party DENK also recently called for changes to street names; the activist group De Grauwe Eeuw (the grey age) carried out a more concentrated campaign, with limited success. As Flor concludes, “I would say for now these talks remain seen "too radical of a change" by mainstream society.”

****

It’s very likely that not everyone who lives and works in the Indische Buurt or the Transvaalbuurt feels a connection to the histories to which their neighbourhoods allude; it’s possible that many people are altogether unaware of these histories. For exchange students in particular, it might seem unnecessary to become overly immersed in such stories: doesn’t everyone have their own experience with injustice, their own idea of how history should change, their own communal mission?

Nevertheless, in a city and country with such longstanding imperial and international connections, it’s important to notice that history is all around us and that it might be told in a way that does violence to the most vulnerable people in the story. Waiting for the tram on Molukkenstraat, we need to keep in mind that this street owes its current existence to a small archipelago a hemisphere away; to generations of people whose lives were irreparably changed because powerful men wanted what they had.

Dank u wel to Anabelle, Chantal, Flor and Una for all your help with this post!

Shanela Ranaraja

<p>My name is Lalini Shanela Ranaraja. I grew up in Sri Lanka, a tropical island-nation blessed with perpetual summer, and yet I ended up going to college nine thousand miles away, in Rock Island, Illinois! I’m studying anthropology, journalism and creative writing because I couldn’t pick just one. In my spare time, I dabble in languages (I speak four), browse art supply stores, and people-watch. I require at least one long, rambling walk a day, even if there’s eight inches of snow on the ground.</p>