Within the past few years, my home university implemented a seemingly progressive and inclusive administrative effort, allowing students to add their preferred names and gender pronouns, which will appear on class rosters and other administrative systems and therefore allegedly avoid misnaming or/and misgendering students. I remember the day when I logged into my students account and saw the tab that allowed me to put down my preferred name. People in China call me Yu Chen, so my last name comes before my first name. I put down “Yu Chen” as my preferred name, only to find out the following day that my name appeared as “Yu Chen Yu” in the class roster. The professor visibly hesitated when she saw my name, and continued to call me Chen. I realized that such a seemingly inclusive movement still assumes everybody goes by their first name and blatantly marginalized the people that do not fit in such a norm.

To help you understand the story better, here’s a short explanation of how to address Chinese people properly. In China, if someone’s name has three characters and you’re close with them, it’s totally okay and common to call someone by their first name. However, if someone’s name had two characters (such as my name), everyone will address the person by their last name and then first name, except when being in an intimate relationship with that person.

I went by Chen for the first two years of university. After the incident at Columbia University where East Asian name tags in dorms were ripped off and the circulation of an online video called Say My Name, I reversed the way my name is written on social media and made it clear that I wanted to be called by my full name. Thinking that the worst would just be having to teach others how to pronounce “Yu” properly (because “Yu” is not pronounced as “You” at all), I was wrong; that week, I was greeted by awkward “Hi You”-people assumed Yu was my first name and how I would like to be called instead. I decided to give up and continued to introduce myself as Chen.

I somehow decided to go by Yu Chen again when I arrived in Rabat-I cannot articulate why. I guess I wanted to try again because I knew I didn’t know anyone in this program and I would only stay in this program for four months so it would be a good experiment to see what would happen if I introduced myself as Yu Chen from the very beginning.

It actually felt a bit odd at first. I guess because I’ve been so used to being called Chen in the United States. In a French taught class, “Je m’appelle Chen” just slipped out of my mouth.

And as expected, my name is hard to learn. A lot of people cannot pronounce “Yu” properly and just call me You Chen. When staff members looked at the roster and called my name, they always said Chen. Very randomly, I had a professor who thought my name was Lee, though nobody in the class has Lee in their name. But I did surprisingly find that a handful students and some staff members pronounced my name perfectly. I was also super lucky to be in a cohort of students who are not U.S-centric at all and are genuinely willing to learn my name and about my background. More surprising, I found that the students who mispronounced my name at first actually figured it out somehow and pronounced my name correctly after a while.

In China, most of the time, names carry significant meanings that parents wish to go with their children throughout their life. Names sometimes carry deep meanings and have references to ancient Chinese literature when parents are well-educated. My name, on the contrary, has no sophisticated meanings. I inherited my last name from my father, and my first name means morning, simply because I was born in the morning. But I love my name. Whenever I think about it, I think about that morning when I was born, how my mother, who never attended school, and my father, who dropped out of high school due to financial hardship, struggled to come up with a significant name.

I found that for the past two years in the United States, I’ve been trying to hard to have an American accent and pick up American slangs, while nobody knows my real Chinese name. I also realized that I tend to Americanize my first name whenever I introduce myself-the “ch” and “e” are pronounced a bit differently in Chinese and English. I think about me being drunk at different parties, laughing out loud and feeling happy when told I was really Americanized.

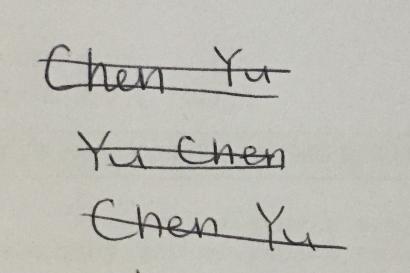

But now I just want to be me. Now I write my name in the order that makes sense to me, followed by my full name in real Chinese characters. I almost forgot that I’ve always been really good at Chinese calligraphy.

Chen Yu

<p>Speaking fluent Mandarin Chinese, English, and conversational Czech, Yu Chen is currently looking to perfect his French during his upcoming semester abroad in Rabat. Passionate about revealing social and structural inequalities around the world through film and media, Yu Chen is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Gender & Sexuality Studies and Digital Media Production.</p><p>Previously, Yu Chen has studied environmental issues in Okinawa, conducted research on social practice art in Puerto Rico, exchanged at the Film & TV School of Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, and tasted 44-year-old homemade Serbian Rakija in Belgrade.</p>