I finally embraced the American student studying abroad aesthetic and brought a suitcase to class. A carry-on—lest anyone be alarmed; I am not traveling back to the U.S. for another seven weeks—and the class was short and the coming day long, so it followed me and a bag of “Literatura Freiburg” loose-leaf tea (Mitbringsel: small gift for my host) to the train station, where we bought a cappuccino and a bottle of back-up water and waited for the ICE 370 to Prague.

The University in Freiburg—and with it, the Freiburg IES Abroad program—observes “Pfingstpause” for one week every summer semester: a German sort of spring break that corresponds with the Christian holiday Pentecost. Students typically take the break in classes as a chance to travel (several of my roommates took a gleeful road trip to the beaches in southern France) or catch up on work (one of my classmates noted with a pang that our final exam—introduction to the study of literary literally everything—is marching ever nearer). Many students travel home to visit family and friends. In any case, there is less time spent at a desk and far more time spent grilling bratwurst or licking ice cream cones or drifting in and out of sleep in the sun or doing all of this in turns in the park.

I will admit, I regarded the prospect of a week without classes with as much skepticism as I did delight. Certainly, I craved a break from the hectic literary theory lecture schedule, and from writing about exiles. I looked forward to waking up every morning with no mad dash bike ride and hasty oatmeal-in-the-microwave toothpaste and instant coffee breakfast. But I was wary of the trade-off, which is to say: the next week would still be a busy one, just this time in a different way.

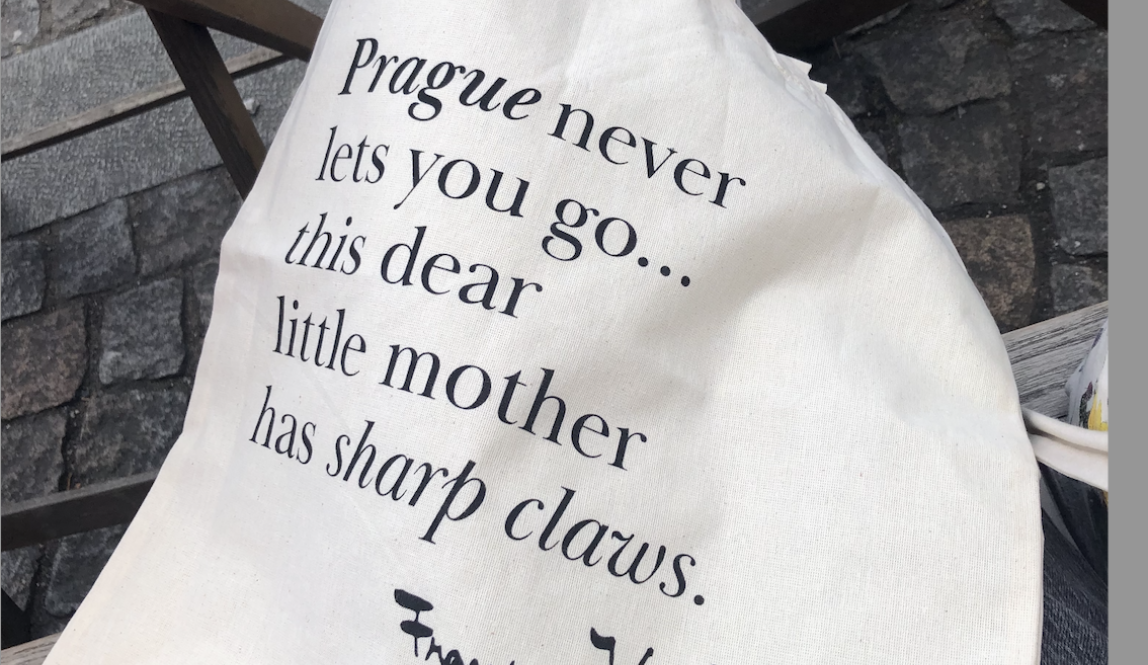

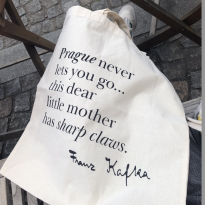

After a lifetime of stories passed through generations and tea-colored photographs and old, faded handwritten letters I finally traveled to the country and the place where my great-grandmother spent the first two and a half decades of her life. And it was exhilarating.

I arrived under a sky strewn with stars. I was stiff after sitting on a duffle bag for hours (an off duty Czech military officer caught me wandering aimlessly looking for a seat in Dresden and offered his enormous duffel bag with the generous offer: “for sit”) and hungry for something more filling than paprika lentil chips and whole carrots. A relative of mine—my second cousin twice removed I believe—graciously met me at the station with her young son—my second cousin three times removed—and a humbling string of perfect English sentences.

Markéta and Krystof and Markéta’s mother Jana folded me into their family, beginning with a bowl of pesto gnocchi in their cozy Prague flat as soon as we returned from the station and a walking tour of the city the following morning. I wa s touched, and I quickly learned not to be surprised.

Over the course of my week, I met a number of relatives—some of them old, many of them young, and all of them warmly offering history and hospitality. I spent three filled days in Prague, and three in a smaller city called Hradec Králové. In both cities I took my job of flâneuse very seriously. Out of necessity, because I did not have cellular data and therefore had no use of my phone, I watched street signs and tracked whether I was lost by the number of times I passed the same shop selling chimney cakes.

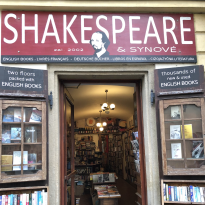

In retrospect, this trip was an extraordinarily short one. But it didn’t feel like that. It was filled to the brim with experiences—new ones, validating ones, intellectually challenging ones, family ones. I came to the Czech Republic mainly on research for my undergraduate thesis, which I will spend the remainder of my time in college—when I am not running around doing the myriad things that American students do on the daily—writing. My thesis, very broadly speaking, is based in Prague’s rich literary history. The highlight of my time in Prague (the highlight, perhaps, of my time abroad so far) came to be because of my thesis.

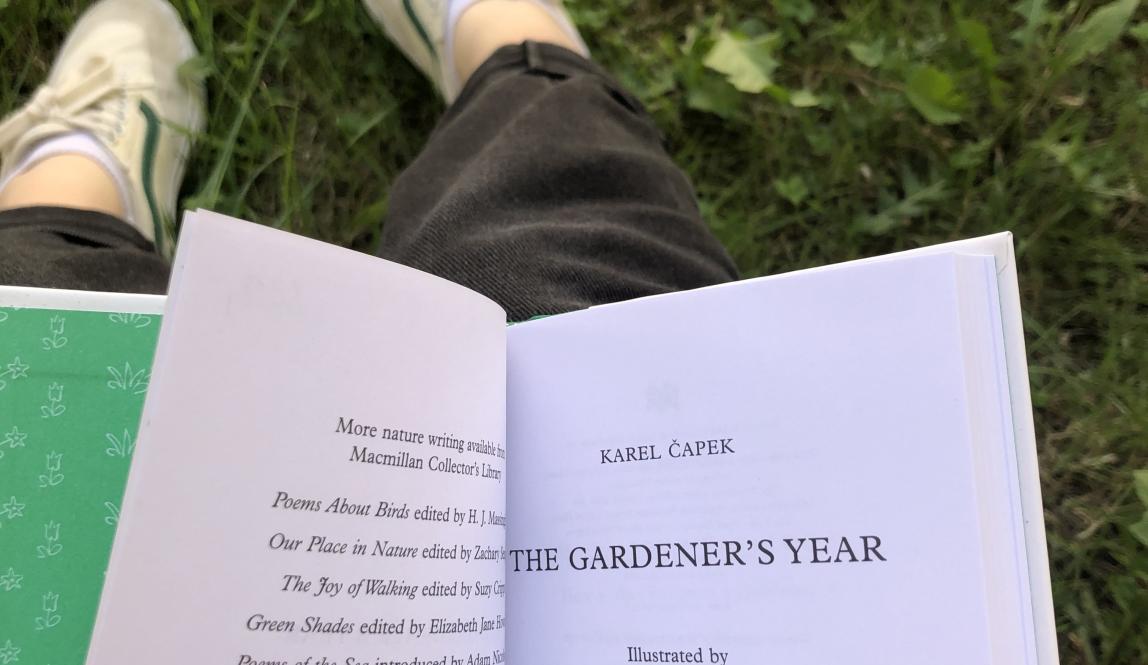

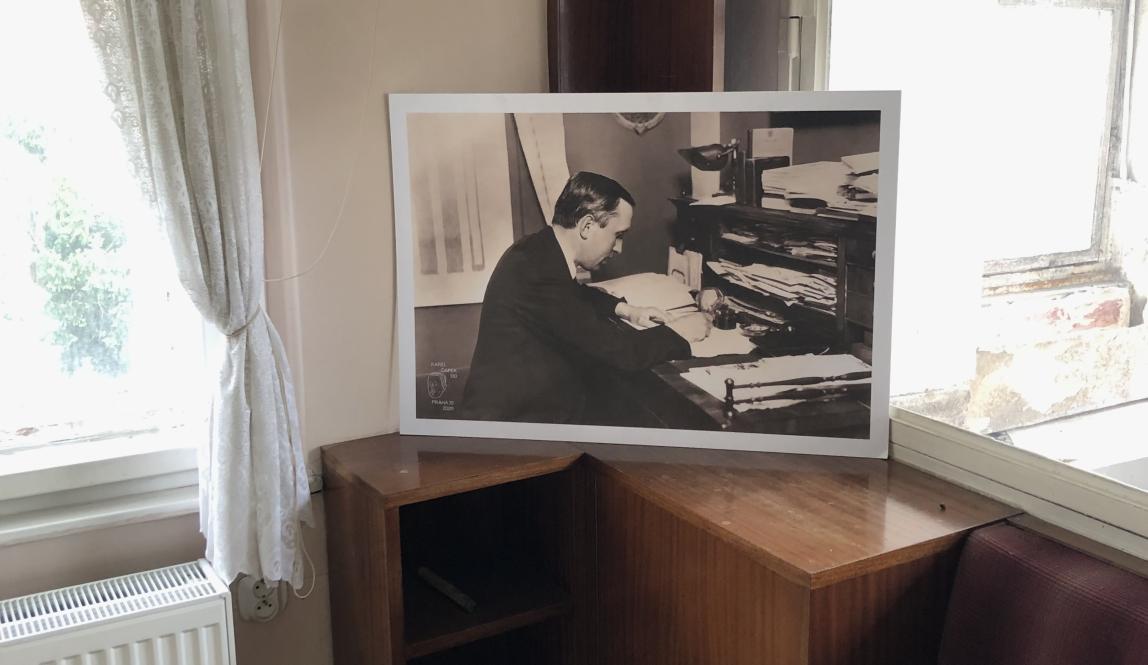

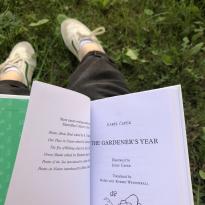

Part of my research involves looking at the reception of twentieth century Czech writer Karel Čapek’s work in the Czech Republic and, in its translated form, in the U.K.. After some digging, I discovered the house where Karel and his brother Josef Čapek lived until their deaths (both died in the final months of the Second World War). It appeared that the house was now a museum—at least, I thought it was. The webpage, after I plugged it into my friend “DeepL” said something about “construction” and “Prague architecture” and “patrons.” Anyway, it had a “contact us” button so I clicked that and wrote them to inquire whether it would be possible to visit the house. I received an answer within the hour. The consensus: “We do not offer any tours inside of the buildings presented” but “There is for sure a possibility to contact [the municipal district] which has the villa in the administration. I am sure they will let you in for research purposes.” A few emails later, and I was responding to the architect (it turned out the house was indeed under construction) to confirm the time he graciously offered for a personal(!) tour of the villa. It didn’t feel real. “I first have to check with the mayor tomorrow,” he wrote, in German. The mayor. Must be the executive in charge of the reconstruction. A minor flaw in vocabulary, lost in translation via our mutual second language.

It was the actual mayor. It was an excellent tour. I saw the place where Čapek’s desk stood, and the ship-like cabin that was his bedroom, and the several miniature greenhouses where he kept his plants, and the wood paneled sitting room where the Czech intellectual and political group, “The Friday Men,” met each week to discuss literature and the state of Europe and probably smoke tobacco pipes. None of it was furnished, and I was wearing shower caps on my shoes to protect the floor, but there was a sizzling magic about the place like if I just opened that door, I would see Dašenka, Čapek’s jack Russell terrier, wagging her tail expecting a walk. The mayor explained that there is a team of designers working on the villa’s restoration so that it can eventually become a museum. The architect showed me floor plans of the original interior. I ran my hand along the back of Čapek’s sturdy wooden desk chair and gazed into the garden where the wisteria grew to the third story window. And when I left, I walked through the same door which Nazi officers did when, after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia—two months after Karel Čapek’s death, they tried to arrest this author, this keeper of plants and goldfish, this “public enemy number two.”

I am beyond grateful for this experience, and I am well aware of the generosity of those that supported my Czech escapade. Both the mayor (1. Místostarosta, Ing. Tomáš Pek S.E.) and the architect (Ing.arch. et Mgr. Ján Vašek) offered to help translate materials for my project, and I’m pinching myself because how amazing is that!

A special thanks to my wonderful big extended family in Prague and Hradec Králové for welcoming me into their midst and feeding me vegetarian lasagna (yes, it’s real food!) and taking me to old castles that look like they belong in Camelot.

It is not lost on me that this is also an experience quite specific to already being in Europe. A huge thanks to IES Abroad for making my semester on this marvelous, multilingual continent possible.

And to those still reading—

Until next time, C

Carolina Weatherall

I like telling stories and writing long-winded essays about my cultural observations. I generally wind up where there are books, or people talking about them, or—better yet—people celebrating queer, feminist or minoritized voices in twenty-first literature.